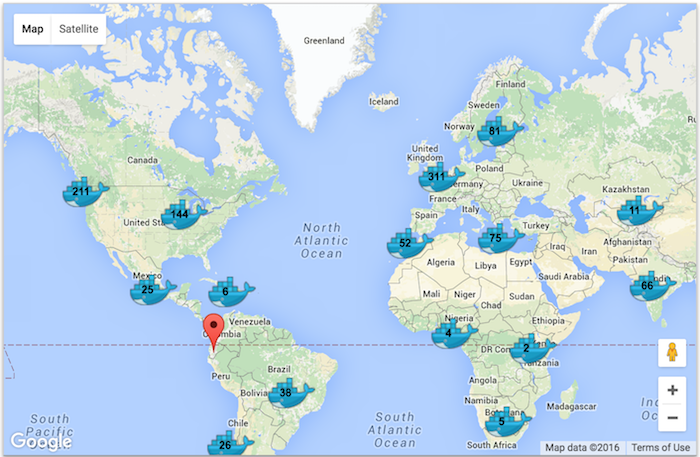

For Docker’s 3rd birthday, the Docker team decided to organize a challenge to teach people Docker, and hopefully have some fun at the same time. It was a great event, with over 1180 people completing the assignment participating in 220 locations around the world.

In this article, we will describe the way we leveraged Docker tools to create a platform capable of handling thousands of requests and testing more than 10,000 containers.

Each participant went through a tutorial and then built a voting app. Within that app, an HTTP API responded with information about the participant. Once a participant built the Docker images, they pushed them to Docker Hub, and submitted an entry to the dockerize.it website. This was done with an HTTP POST containing the user’s Docker images and information. This in turn triggered a series of events behind the dockerize.it website that lead to the running and testing of the user images, and the marking of the entry as failed or successful. Soon as a submission was marked successful a pin was displayed on the map. Pins were aggregated according to the zoom level.

Requirements

Based on the specifications for the birthday app, we realized we had three main challenges:

-

We had to be flexible and able to deal with a surge in participant submissions. We had rough estimates about the number of events and people but we couldn’t know for sure the rate and number of submissions. Our app would have to account for a scenario where we ran out of capacity for testing the images by queuing the responses.

-

The participant’s containers could not compromise the responsiveness nor security of the dockerize.it application. Since this was an open challenge, there was a risk of having malicious containers, so we had to contain and recover from a possible denial of service or other attacks.

-

100% availability was paramount. Encountering downtimes during the events was not acceptable. Hence, failover and scaling up/down had to be performed with full transparency for the users.

We are big fans of automation and Agile methodologies, and we have invested a good deal of effort along time in a set of tools that allows us to work like that. Since the early days of Docker, it has been central to our work in terms of delivering software. And although the ecosystem around it has been moving very fast, Docker itself has remained and solidified as the standard unit of delivery.

We chose to run the application on DigitalOcean, our preferred cloud for quick one-off projects. DigitalOcean, offers fast deployment times and a straightforward API, which makes it easy to iterate with our Terraform deployment plans.

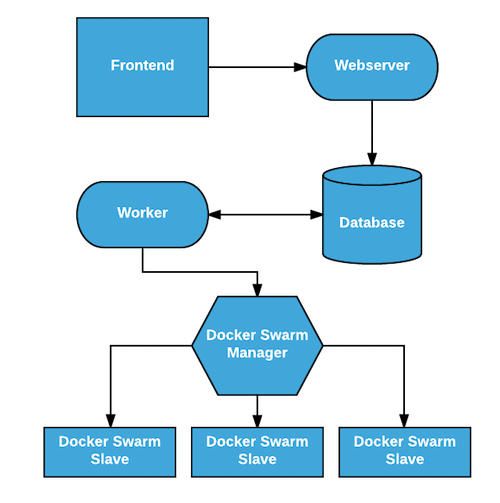

The core application

The core of the application consisted of two components:

-

A user facing component (API) with two endpoints: one for sending a competition submission and the second for retrieving various stats about the competition

-

A background component (Worker) that tested user containers for compliance with the competition rules.

The API received a request from the user and ran sanity checks on the submitted data. If the data passed validation it was saved in a MongoDB database and a response was returned to the user containing a unique ID. The API was written in Python using Flask and ran using a standard Nginx + Gunicorn setup. Nginx was setup to terminate SSL connections and we used the excellent Let’s Encrypt service to generate certificates for the website.

In the second phase of the process, the Worker took an unchecked user submission from the database, downloaded the user created Docker images, ran them and validated that they complied with the competition rules by probing port 80 and checking the result they return. The Worker also updated the status of the submission along the way so that users could check the status of their submission through the API. The Worker was written in Python and ran in multi-threading picking submissions periodically from the database and interacting with the Docker API to run and test the user containers. Waiting times for checking new submissions was computed dynamically based on the number of submitted images between two consecutive checks.

As you can see, the actual verification of the submission was done asynchronously in the background. While the API had strict availability requirements, the W****orker was more tolerant of failure and could be more flexible about when it processed the user submissions.

Building for resiliency and workload flexibility

Building systems that deliver on their functional requirements is fairly straightforward (especially in this project), but delivering on operational requirements is considerably more difficult.

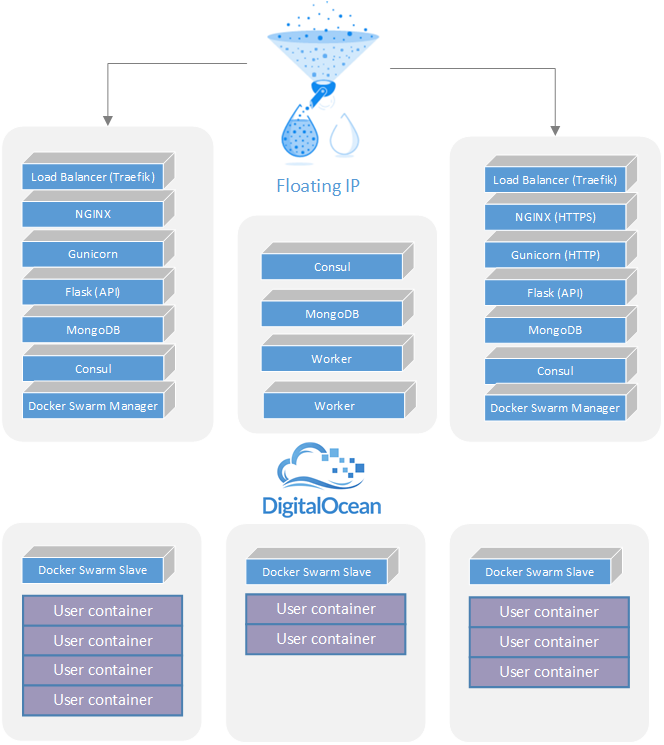

Even though we kept the application as simple as possible, satisfying the requirements - especially for security and availability - meant that we needed more than 1 machine to distribute the various components of the application. Since both MongoDB and Consul require an odd number of instances to form a quorum, we went with 3 machines for running the application and its dependencies, and 3 machines for the Swarm cluster running the user submitted containers . As you can see in the diagram below there was a clear separation between the machines that ran the application and the machines that ran the user containers.

The most important goal in splitting these 2 groups of machines was to isolate user submitted containers from the main application that processes user submissions. Since users controlled the content of the containers that they submitted, running them on a separate set of machines reduced the risk of having the whole application compromised or DOS-ed by a user with ill intentions. Another important difference was the availability requirements for the 2 groups of machines. The application could tolerate running without having any Swarm agent nodes but it could only tolerate partial failure in the group of machines that ran the application itself.

Workload flexibility

In the first requirement we recognized that we could not estimate the amount of user submissions and how they would be spread over time, so we needed a way to easily expand or shrink our capacity to run containers. Docker Swarm is a great fit for the problem because, as stated on their website, “It turns a pool of Docker hosts into a single, virtual Docker host”, which meant that we could add or remove hosts to the cluster, depending on how much capacity was required at that point in time. Swarm also exposes a Docker compatible API for which there are a large number of libraries available, including Python. And finally, multi-host networking allows the creation of networks that span multiple hosts. This proved very handy for testing the user containers. Our Worker could easily open a HTTP connection directly to a user container running on a different host without messing with exposing ports and firewalls.

Swarm is comprised of two types of components: a manager and an agent. The agents run on machines that provide the cluster with capacity, and connect to the manager, which schedules containers across the available machines. We used Swarm’s high availability mode, with the help of Consul. You can read more about how it works here.

By accessing the the Docker API on the Swarm manager, our Worker could transparently run containers on the Swarm agent nodes and have direct network access to those containers. Now it is easy to understand how the worker performs the verification of the user submissions:

-

A submission is retrieved from the database, which contains the name of the user built Docker images (host on Docker Hub)

-

The Swarm manager is instructed to download the images from Docker Hub

-

Once the Docker images are retrieved, a call is made to the Swarm manager to run the containers, which returns the IP allocated to the running container.

-

Worker tries to establish an HTTP connection to the container (using the IP retrieved earlier), and check if it returns the correct information.

-

Submission is updated in the database, based on the result of the previous step.

If anything went wrong in the mentioned steps, the submission status was updated accordingly so that the user knew what went wrong. For example, many users submitted entries with non existent images or images that failed to start. In such a situation, the user would check the status of their submission,see that it failed, and retry their submission until it would be successful.

Did we take advantage of the scalability capabilities of this setup? Kind of. We started with 3 nodes in the Swarm cluster and that proved to be enough in terms of capacity so we never added more nodes. But now that the application sees very little usage, we removed two of the Docker agent nodes and that was trivial to do.

Resiliency

Starting top - down, our entry point into the system was a DigitalOcean Floating IP, which is a nice feature from DigitalOcean that allows you to map a public IP to any droplets within the same datacenter. The Floating IP can be moved either manually using the DigitalOcean web interface, or by doing an API call. In our situation we used it to quickly switch the IP to a different droplet in case our load balancer couldn’t be reached. This feature also proved useful for doing controlled upgrades.

As a load balancer we used Traefik. Although it is a young project its appeal lies in the way it does backend discovery. It can dynamically configure new backends and routes based on Docker container tags, or entries in a key-value stores like Consul or Etcd. We chose the first option, and tagged each Docker container running the API application (Nginx + Gunicorn), so that Traefik would pick it up and start routing traffic to it.

All user data was stored in MongoDB, running a three member replica set. We had several API and one Worker container running on two of the management machines, and capacity to start more on the third. Both the API and the Worker used the PyMongo library to connect to the database, and the beautiful thing about this library is it’s ability to automatically maintain a connection to the replica set, by transparently connecting to a newly elected MongoDB server. In order to take advantage of that feature PyMongo needs to be aware of all the server in a MongoDB replica set.

As mentioned earlier, Swarm ran in high availability mode by using two managers, doing primary elections using Consul. Once the election of the primary Swarm manager is completed, the details of that manager (host + port) are stored in the Consul key-value store. We leveraged that information in the Worker, to be able to always connect to the primary Swarm manager, regardless on which of the management machines it was running.

In case of machine failure, the DigitalOcean floating IP would have been moved to a working machine, and the API and Worker instances on that machine would have continued to function correctly because the database and Swarm manager would have failed over to one of the other working machines.

Luckily none of the machines failed during the Docker Bday events, but we still found this setup very useful. During one of the events happening in China we had a big surge in users and we started getting notifications that one of the machines is overloaded. It turned out that it was the machine where the DigitalOcean floating ip was configured, and where all the user traffic ended up. It was a case of resource starvation and we realized that we under-specd our management machines. We decided right there to upgrade each management machine, which required a few minutes of downtime for each one. One at a time, we proceeded to change and apply the Terraform definitions for the management machines, which took them offline and then back online once the upgrade has been performed. The whole process was trivial and went unexpectedly smooth, and for the first time the extra time spent in building a redundant setup paid off.

What We Learned

Looking back at the development process, we had a lot of fun building the application for Docker. Using Docker to bridge the gap between the development process and running the application in production has been a boon for us, and we couldn’t imagine working without it. Docker has rapidly become a standard unit for packaging and working with software, and similarly to the trusty shipping container, has spawned an ecosystem of tools that have changed our field for the better.

Docker Swarm

Even though we had no previous experience with Docker Swarm and its new networking feature, it was easy to set it up and run thousands of containers on a cluster of machines. Our favorite feature was the capability to have end-to-end connectivity between containers running on any VM, without having to deal with port forwarding or firewall rules. We will be using Swarm in future projects and are looking forward to seeing a web based UI developed for it.

Building and deploying applications in containers

Docker makes building and deployment of application much easier through proper image tagging, clear segregation of services, portability and last but not least the comprehensive directives available when building a Docker image.

Streamline development process

In a traditional environment testing a software application we would have to rebuild all components in order to set up a relevant testing environment (sandboxes). Each of these environments would have their own configuration, environment variables, libraries etc.

Using containers we managed to streamline the development flow. This was possible because we were able to isolate the applications and reduce dependencies on modules, libraries etc.. This ensured that the applications are identical regardless of the Development stage they were in.

Community support

During the whole Docker Birthday event, various questions were raised and we were surprised to see the community being extremely responsive and helpful. From newbie mistakes to more complex issues encountered when trying to go the extra mile, all of them have been solved with a great support from Docker community.